What are the relationship between school discipline and academic performance in Christian seminaries versus ordinary secondary schools in Tanzania mainland

Background to the problem

The provision of quality education and training is the ultimate goal of any educational system. This goal can never be achieved without school discipline. Discipline in school is a very important aspect towards academic excellence, while lack of it usually gives rise to a lot of problems such as lack of vision and mission, poor time management, irregular attendance and punishment. By definition discipline refers to the ability to carry out reasonable instructions or orders to reach appropriate standards of behaviour. It is understood to be that abstract quality in a human being which is associated with and manifested by a person’s ability to do things well at the right time, in the right circumstance, without or with minimum supervision (Ngonyani, 1973:15).

Various studies have been conducted on issues pertaining to schools’ academic performance, such as those by Malekela (2000:61), Galabawa (2000:100) and Mosha (2000:4). They have pointed out some factors that lead to varying levels of performance in schools, including availability of teachers, availability of teaching and learning materials and language communication. A few scholars such as Omari (1995), Okumbe (1998) and Galabawa and Nikundiwe (2000) talk about school discipline as one among aspects that influence performance in schools. School discipline is an essential element in any educational institution if the students are to benefit from the opportunities offered to them. Omari (1995:38) argues that it is difficult to maintain order and discipline in schools where teachers have no space to sit, prepare and mark students’ work. In other words, Omari (1995) supports the above scholars that availability of teaching and learning materials has an impact on school discipline. Galabawa and Nikundiwe (2000:203) argue that hardworking and devotion on the part of teachers and students is among of the factors for school success. Furthermore, Maliyamkono and Ogbu (1999:72) add that, it is impossible to talk of disciplined teachers and students where there is no cooperation and rapport between the school and the community around.

In addition, it is common to hear parents, teachers and students themselves complaining about indiscipline in schools. The Swahili slogan “huyu amesoma lakini hajaelimika” meaning that “one has attended school but is not educated” is becoming talk of the day in many secondary schools. The reason for such kind of comment is that there is a general impression among the educational stakeholders that secondary school students are undisciplined as they are not abiding by school rules and regulations. Occasionally there are protests, riots and violence and sometimes the police have to come in to intervene to protect school property. Some schools become virtual prisons as they construct huge walls and expensive fences to check abscondment and to protect good students, teachers and property against undisciplined students. For example, in Nipashe news paper of March 30th, 2007 there was a Swahili report “wanafunzi wa shule ya secondari Ikhonda watupwa jela miaka sita baada ya kuharibu mali ya shule” meaning that “Ikhonda secondary school students sentenced to six years in jail for destroying school property”. In addition to that in 2008, Mtanzania May, 30th had the title: “wanafunzi wa shule ya sekondari Mwakaleli Mbeya wafanya fujo na kumjeruhi mwalimu wao” meaning that “Mwakeli secondary school students in Mbeya region riot and injure their teacher”. Ohsako (1997:7) argues that violence is a sensitive issue that provokes anxiety, arouses emotions and has negative impact on school performance.

Despite the presence of rules endorsed by the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training they are not followed by many of the students and their teachers in some government and private schools, who misbehave wherever they are outside the school environment. As Omari (1995:25) observes, the most important thing is not so much to have written rules pinned in the office of the head teacher or discipline master as to have rules actually implemented. School rules and regulations should facilitate administrative work, should focus on the creation of a good atmosphere for teaching and learning.

For several years now there have been concerns by various people and groups regarding the deterioration of the quality of education in secondary schools. Against a background of these concerns and complaints, one is duty-bound to avoid blanket blames and generalizations but to take an objectively discriminating analysis of those educational 23

institutions whose quality has really declined vis à vis those that have maintained or even raised the standards; of the characteristics of such varying categories of schools; the circumstances surrounding differential performance among them; as well as the varying levels of discipline associated with different school categories.

Generally, religious denomination affiliated schools, i.e. seminaries, have frequently been associated with claims of good discipline (hence with academic success) as compared with public and other private schools. To verify such a claim it would be necessary to take an historical perspective of school performance at a national level, by school category, over time.

Table 1.1 comprises a list of the first ten (best performing) schools in the national examinations over a 15-year period after every interval of three years from 1992 to 2007. It is observed that, for each of the year indicated, the majority or else a considerable number of these best schools are Christian-affiliated seminaries, while only a few such as Ilboru and Mzumbe government-owned schools, rank among them.

On the other hand, Table 1.2 lists ten least-performing schools in national examination results for the same period. While almost all of them are public schools directly owned managed by government or directly owned and managed by local communities or trusts, there is not a single seminary counted among them.

On the basis of the factual data in Tables 1.1 and 1.2 above, there was a need to investigate any possible influence that might exist between type of school, ownership and management characteristics and academic performance or success.

Statement of the problem

The survey of the results of the national Form Four Examinations in Tanzania for 15 years now, from 1992 to 2007, indicates an undebatable dominance of Christian seminaries in the top positions.

Despite numerous studies that have been carried out such as those by Malekela (2000:61), Galabawa (2000:100), Mosha (2000:4) and Omari (1995:38) that look for factors associated with academic performance in schools, little has been investigated on discipline, particularly with respect to religion-affiliated institutions, in this case Christian seminaries in comparison with ordinary secondary schools. A study into this issue is thus imperative that would focus on how school discipline can be identified or defined, factors of its existence or absence in schools, and the principal determinants of school discipline in relation to academic performance in schools. The issue of discipline has become a matter of concern to many educators today. There is a need to address the issue of indiscipline in schools if they are to meet the academic and social needs of all students and the society in general. It is generally accepted that schools differ in their effectiveness as places of learning. As one single category, seminaries have been performing well in the sector of education when compared with those under public or community ownership; but little has been published on the nature and level of school discipline as a causal factor, or even as a co-relate, of academic success in these institutions. It is expected that such a study might lend some insights and lessons to educators and other schools that are high or least performing as well.

Purpose (objectives) of the study

The general purpose of the study was to examine school discipline as the determinant of academic performance in Christian seminaries in comparison with other, ordinary secondary schools. Specifically, the study attempted:

To examine the extent to which school discipline influences academic performance in schools;

To investigate how school rules and regulations are formulated and enforced in schools

To examine the extent to which the management order and style for the school plays a role to maintain school discipline.

Significance of the study

The significance of this study can be judged by the following advantages to be accrued:

Firstly, the study essentially generates knowledge on what actually parents, teachers, students and education officials perceive as to the importance of discipline in academic performance in schools. Secondly, it establishes a base for formulating rules which can be adhered to by teachers and students. Thirdly, it serves as a guide to teachers, community, education officers and administrators as to what key issues are related to school discipline for purposes of enforcing in school situations. Lastly, findings act as stimuli for further research related to the school discipline and performance in general.

Theoretical basis

For the most part in the period of education worldwide, the concept and knowledge of discipline was narrowed and circumscribed. The idea of punishment was predicted upon the punishment model. Traditionally discipline in school was mainly associated with punishment and fear. Punishment was considered necessary as a disciplinary measure in the schools and therefore used as a means to maintain “good discipline,” often referring to conformity and order in schools. In this case, punishment as a social institution is intended to control, correct or bring into the desired line the behaviour of an individual or group of individuals. However, corporal punishment was often problematic and it is still a problem today, unless strictly monitored. Gossen (1996:30) and Omari (2006:131) argue that punishment does not teach the correct behaviour, it destroys even the opportunity to demonstrate the acceptable behaviours. From the age of eighteen onwards there is a growing opposition to any use of physical force in disciplining individuals.

This view brought to the surface two opposing views on discipline and these are in line with Douglas McGregor’s Theory ‘X’ and Theory ‘Y’ assumptions about people (McGregor, 1960:3-57). There are those people who regard discipline only as a punishment as applied to Theory ‘X’ assumptions. In schools, for example, a teacher or a student just does not want to follow the code of behaviour. To make them disciplined threat punishment, control, rewards and incentives have been seen to be the most effective measure in maintaining discipline in schools.

Another group of people are those who are against corporal punishment. Among these are educational philosophers and psychologists (Wilson, 1971 and Newel, 1972). They look at discipline as a process of encouraging teachers and students to behave more uniformly, towards meeting the objectives of education. This group of people are applying Theory ‘Y’ assumptions about people. They argue that external coercion and control are not only means for bringing about effort toward organizational objectives. Management can not provide a man with self respect, but to create conditions that would encourage self-discipline. Punishment in school according to them creates in the child a tendency towards blind imitation and fear. On the other hand, Omari’s conceptual framework for Quality Assurance (1995:25-45) was also integrated with Theory “X” and “Y” assumptions by providing the basic school and extra-school inputs to reveal connectedness in bringing out influence of school discipline and academic performance. Within McGregor’s Theory “X” and “Y” assumptions and Omari’s Model, the relationship between “discipline” and “academic success” in a school setting can be construed as per researcher’s conceptual framework in Figure 1.1.

As the diagram (Figure 1.1) indicates, a minimum reign of punishment, plus a maximum regime of intrinsic self regulated discipline in individuals, create a learning environment and conditions that, if complemented by desirable basic school and extra-school inputs, lead to intended positive learning outcomes.Research tasks and questions

Three research tasks guided the researcher to obtain information relevant to the problem. Each task was informed by relevant questions:

Research task one:

To examine the extent to which school discipline influences academic performance in schools

Research questions

What are the common discipline-related problems among teachers and students that tend to hinder smooth teaching and learning in schools?

Why do teachers and students tend to violate schools rules and regulations?

Research task two

To investigate the ways school rules and regulations are formulated and enforced.

Research questions:

Who are involved in the formulation of school rules and regulations?

How are these rules and regulations made clear and agreeable to both teachers and students?

What kind of punishment is given when students break school rules and regulations?

Research task three:

To examine the extent to which the management of the school plays a role to maintain school discipline.

Research questions:

How does the management of the school ensure that teachers and students keep discipline towards fulfilling their duties and responsibilities?

What methods does the management of the school use to make sure that there is an amicable relationship between the school and the community around?

What type of consideration does the school management take into account on the choice of school premises?

What strategies do teachers use to make sure that their students perform better?

Definition of the key terms

Discipline refers to a form of the logical and educative order which must be learned if one is to understand what is involved in doing something. According to Ngonyani and Manase (1968:), it is understood to be that abstract quality in a human being which is manifested by person’s ability to do things well at the right time, without or with minimum supervision. This study has adopted this definition.

Academic performance is an ability to display through speaking or writing what one has learnt in the classroom. Academic performance usually encompasses a range of factors such as knowledge and skills, qualification of teachers, teachers’ and students’ commitment and success of school management (Gipps 1991:42).

Seminary is a religious training college or institution for priesthood ordination. In the common context in Tanzania, a seminary is a secondary school which offers both academic and religious instruction and may lead either to priesthood or to higher levels of academic training and qualification.

Rector is a member of the Christian, particularly the Roman Catholic clergy who is in charge of Catholic congregation or college. However, in this research the term Rector will only refer to the head of a Christian seminary.

Congregation: According to this study, a congregation is a group of people with common faith living together in an association for religious purposes.

Delimitation of the study

This study was focused only on the influence of school discipline and academic performance in Christian seminaries in comparison with ordinary secondary schools in Tanzania mainland. The researcher of this study used only ten (10) schools (six Christian seminaries and four ordinary secondary schools) which delimit the representativeness and generalizability for the whole situation at the national level.

Limitations of the study

The study encountered some limitations; in most of the sampled secondary schools respondents were either busy preparing for mid term tests or on mid-term break and Form Four Mock Examinations. For example, Kwapakacha Secondary, Form Four were busy for Mock examinations other preparations. To overcome this limitation, only Form Three were contacted for the study. Maua Seminary Form Three were in mid term break and so Form Six students were included to bridge this gap. On the other hand, some interviewees in both types of schools were busy marking examinations and other official responsibilities and some of the heads were not available. The researcher continued to follow up for an extra two weeks until the appointments were fulfilled. This affected the time schedule though in the end did not alter much the planned accomplishment procedures. However, it is hoped that in concentrating on a small sample of church-affiliated institutions, vis à vis another kind of schools, some unique observations were made that might have qualitatively different bearing on practice on the educational system in general.

Organization of the study

The study is organized into five chapters. Chapter one is concerned with the problem which informed the study and its context and defines the need for this study. Chapter two focuses on the review of literature relevant to the study. Its main concern was to identify the knowledge gap. Chapter three presents methods of investigations and procedures to address the problem and the knowledge gap. Chapter four discusses the research findings of the study which are presented under sections according to research tasks and questions. Chapter five presents a summary of the study and findings, conclusions and recommendations for practical actions as well as for further study based on the research findings.

Literature review

The previous chapter attempted to justify the rationale for this dissertation. In this chapter the literature relevant to the relationship between school discipline and academic performance in schools is reviewed accordingly. The chapter is divided into sections: the concept of discipline, types of discipline and different views of school discipline in the global context, and principles of setting good practice in setting disciplinary actions. It also surveys the determinants of school discipline and finally identifies the gap to be filled.

Concept of discipline

Traditionally, discipline in school administration meant punishment that is pain and fear. To some discipline can connote something negative as obeying orders blindly, kneeling down, doing manual work, fetching firewood and water for teachers and parents, caning and other forms of punishment. Bull (1969:108) associates this as physical discipline that leads to threatening condemnation to a child.

Indeed discipline involves the preparation of an individual to be a complete and efficient member of a community; and a disciplined member of a community is one who knows his or her rights and his or her obligations to their community. This means that the individual must be trained to have self control, respect, obedience and good manner (Ngonyani et al, 1973:15). Okumbe (1998:115) and Galabawa (2001:23) see discipline as an activity of subjecting someone to a code of behaviour that there is a widespread agreement that an orderly atmosphere is necessary in school for effective teaching and learning to take place. Discipline, according to Gossen (1996:25) and Lockes in Castle (1958:126), is reasonable in the eyes of those who receive it and in the eyes of a society as a whole. It is expected that the rules are known by all and are consistently enforced. In order for an action to be good, discipline must also be reasonable. A person is able to deny himself or herself to his or her desires and serves for others.

Types of discipline

According to this study only two types of discipline were investigated: positive and negative discipline as identified by Umba (1976), Bull 1969) and Okumbe (1998). The first type, positive discipline is sometimes known as self discipline. Self discipline is the kind of discipline that comes from the aims and desires that are within the person, where there is no element of fear (Umba, 1976:8). Okumbe (1998:116) relates positive discipline with preventive discipline, providing gratification in order to remain committed to a set of values and goals. It is encouraged self control, individual responsibility in the management of time, respect of school property, school rules and authority, good relationship between students and teachers. Bull (1969:108) associates self discipline with psychological discipline that seeks to reason with a child so that he or she may understand the folly of the particular offence and build up moral concepts.

The second type of discipline, negative discipline, occurs when an individual is forced to obey orders blindly or without reasoning. The individual may pretend to do good things or behave properly when superiors are present but once they are absent quite the opposite is done. For example, a teacher may behave well before his or her head of school, perhaps in pursuit of something like promotion or other favours. Likewise, students may behave well when their teachers are present, but resort to mischief as soon as they are out of sight.

Different views on school discipline

There are different views on teachers’ discipline and on students’ discipline as stipulated in the literature. The first view is that teachers’ discipline is concerned with how teachers behave and conduct themselves. An effective school can be successful when teachers become model of good discipline. Normally students learn by observing how teachers behave. Manase and Kisanga (1978:6) and Cleugh (1968:92) argue that a disciplined teacher is one who abides by his or her code of conduct and employment contracts. He or she is the one who fulfils the expectations of the school as well as society at large.

The second view on school discipline is students’ discipline. It is how students behave in and outside the school. A disciplined student is one who abides by school regulations, respects the school timetable and does what is expected of him or her by teachers (Manase and Kisanga, 1978:16). A disciplined student demonstrates self control, individual responsibility in the management of time, and sensitivity of matters of self conduct and relations with others.

Principles of setting good practice in setting disciplinary actions

The following five are some of the principles as applied in setting disciplinary action in a school (Okumbe, 1998:119):

Prior knowledge of rules and regulations

The educational managers must ensure that all staff members are informed about the terms and conditions of their employment and the rules and regulations of the organizations in which they work. This should be done during orientation or induction course. The students should also be well informed about the organization’s rules and the consequences of breaking them. Gnagney (1969:14-15) and Omari (2006:130) argue that indiscipline is often caused by ignorance of the rules and inability to adhered to multiple and sometimes conflicting rules that frustrate intelligent individuals. When school rules and regulations are not fair and clear to teachers and students they are always broken.

Immediate application of disciplinary action

Educational managers must ensure that any undesirable behaviour either by a staff member or by a student is dealt with immediately so that the offenders can see the close connection between an undesirable behaviour and its consequences. The association between the undesirable behaviour and consequences becomes weak when there is a long term lapse.

Consistent application of disciplinary actions

This is to say that educational managers should ensure that similar offences are dealt with in similar ways. If there are variations in the way similar offences are dealt within an organization there is the likelihood of a general discontent by the clients.

Objective, non prejudiced disciplinary actions

An effective disciplinary action must be on facts not inferences. An educational manager must, therefore, carry out a thorough research to ensure that the offence was actually committed by the said staff or student before a disciplinary action is taken

Allowance for the right of appeal

The right of appeal is very important in democratic disciplinary processes. Staff and students must be allowed to defend themselves against the offence for which they have been charged. Otherwise they may be punished for an offence they never committed.

Determinants of school discipline

Exemplary academic performance is the function not only of one factor but many factors in combination. Several scholars have tried to investigate essential factors that determine discipline in schools. These factors include school infrastructure, the managerial dimension, school rules and regulations, quality of human resources and student-teacher ratio. Proper working of the essential factors depends on school discipline. Absence or improper balance of these may lead to poor academic performance. The following are the principal factors:

Managerial dimension

Omari (1995:39) and Mosha (2006:23) argue that the overall effective management of any school is directly influenced by the way in which its managers allocate resources, communicate with staff, students and the wider community. Mosha (2006:17) maintains that good leadership should be able to establish levels of commitment and accountability systems to ensure this commitment is met. Gossen (1996:26) argues a head who plays the role of an absolute dictator may be direct or indirect cause of deviant behaviours.

Availability and efficiency of school infrastructure

The school infrastructure includes school libraries, laboratories, dormitories, classroom, classroom facilities and teachers’ houses and offices. The availability and efficiency of school infrastructure assures better performance, provides a certain amount of security and builds self-discipline in both the teachers and the students.

Quality of human resources

Any discussion of quality of human resources in relation to school academic performance must take into account teachers’ qualifications on the one hand and students’ selection and admission requirements on the other hand (URT, 1995:41). Quality education can only be provided in a context where teachers are well trained and competent. Omari (1995:31) and Njabili (1999:29) maintain that teachers are expected to be creative, innovative and visionary. Quality of teachers creates security and hope for students to dream for a better future, while a questionable quality of the teacher raises anxiety and doubts among students who, with time, may rise up in protests.

School community relationship

A school, according to Okumbe (1998:10), is a processing device through which the educational system meets the aspirations of the society. The strong relationship between a school and the community, according to Mosha (2006:206), therefore adheres to the principle of transparency and thus tries to maintain discipline and order in school.

Motivational factor

According to Okumbe (1998:40), motivation may include materials offered such as salary, fringe benefits and public recognition. Mosha (2006:208) asserts that motivation promotes group cohesion. Group cohesion promotes a sense of trust and commitment, and such a sense promotes a sense of discipline. Omari (2006:321) maintains that motivation increases competence or personal mastery and self direction.

Regular assessment and feedback

Regular assessment and feedback provides useful information that can be used to judge progress made and they give teachers and students an opportunity to take remedial measures to improve performance. Cleugh (1968:94) and Omari (1995:40) argue that in order to maintain students’ discipline in the classroom children should have plenty of work to do, such as tests and impromptu quizzes.

Effective financing

Mosha (2006:139) and Galabawa (1994:45) maintain that effective financing helps to create a positive school climate. It is a catalyst that makes everyone in an academic institution committed, while inadequate funding may be a source of conflicts in school due to lack of necessary facilities to keep education institutions in normal running.

The number of students vis a vis the number of teachers

A balanced teacher student ratio is of advantage to the students as well as to the teachers. With a balanced teacher-student ratio students have ample time to contact and dialogue with their teachers because of the available time, and control of the class becomes easy. A proportion of one teacher to more than 30 students has been taken as too large, while a teacher-student ratio of 1:20 or less is too small, making teacher virtually under employed. An optimal proportion in Africa is 1:23 and that of the world falls between 1:20-45 (SEDP, 2004:8 and Carnoy, 1998:43).

Literature gap

A few of the studies that have examined the factors of academic performance in Christian seminaries have focused more on managerial skills and availability and efficiency of resources. These studies reviewed included Hemedi (1996), Galabawa et al (2000) and Lyamtane (2004). However, little has been said or investigated regarding a possible connection between academic performance and the state of school discipline both in these religiously founded educational institutions and in relation to (in comparative reference to) ordinary secondary schools, particularly the least (“worst”) performing ones as indicated by national examinations results. The study intends to fill up this gap in the literature.

Research methodology

The previous chapter presented related literature review through which the knowledge gap related to the research problem was identified. This section presents the methodological procedures used in the collection of the relevant data and its analysis to fill the identified knowledge gap. It describes the methods and the procedures which were employed in the process of data collection and analysis. More specifically, the chapter focuses on the research design, geographical setting of the study, population, sample and sampling procedures, methods of data collection, and techniques of analyzing the data. Other aspects include validity and reliability of the study instruments and ethical issues and considerations.

Research approach and design

Research design is the conceptual structure within which research is conducted. It is a logical sequence in which the study is to be carried out, and constitutes the blueprint for the collection, measuring and analysis of data (Kothari, 1990:132). The research employed mainly qualitative approach and with some elements of quantitative approach for examining the extent to which school discipline influenced academic performance in Christian seminaries in comparison with other ordinary secondary schools. The study sought to investigate how both teachers and students were responsive to discipline. The concurrent triangulation approach was deemed relevant as it enabled the researcher to use various methods to conform, cross validate, or corroborate findings within a single study. The study employed largely the descriptive case study design to describe the characteristics of particular individuals or groups. The U.S General Accounting Office (1990) in Merterns (1998:166) defines case study as a method of learning about a complex instance, based on a comprehensive understanding of that instance. The choice of this design was influenced by the purpose of this study as reflected in chapter one. A case study design has an advantage of focusing on “how” and “why” questions (Yin, 1994). Thus, case study design enables the researcher to gather deep information about the relationship between school discipline and academic performance.

Area of the study

The study was conducted among ten secondary level institutions on mainland Tanzania. Six of these were Christian seminaries selected from among the top (best performing) institutions in the national examinations results, while four were ordinary (“lay”) secondary schools selected from among the last (least-performing schools).

Thus guided by documented NECTA results over the past 15 years, the best-performing Christian seminaries selected included Maua, Uru and St. James seminaries (Kilimanjaro region), St. Peter’s and Kasita seminaries (Morogoro region) and Visiga seminary (Coast region). On the other hand, the four ordinary secondary schools selected from among the worst performers academically included Haneti, Pahi and Kwapakacha secondary schools (Dodoma region) and Kashozi secondary school (Kagera region).

Population Sample and Sampling Techniques

Target Population

The term population refers to a large group of people, an institution or a thing that has one or more characteristics in common on which a research study is focused. It consists of all cases of individuals or things or elements that fit a certain specification. Fraenkel and Wallen (2000:103) denote that a population is the group of interest to the researcher from which possible information about the study can be obtained. The targeted population of this study included all students, teachers and heads of schools in Christian seminaries as one category and similar members in ordinary secondary schools as a second category. These were 96 ordinary level secondary schools as indicated in Tables 1.1 and 1.2. When considering the time and financial factors involved in a study of institutions of such magnitude, it was not possible to conduct this study in all such schools in the country. As such a representative sample in the population was selected, bearing in mind that some aspects gained from a representative sample were adequately generalizable to the whole population.

Population sample

A sample is a smaller group of subjects drawn from the population in which a researcher is interested for purposes of drawing conclusions about the universe or population (Kothari, 2004:157). Leedy (1986:210) adds that the results from the sample can be used to make generalization about the entire population as long as it is truly representative of the population. In this study, six seminaries were sampled to represent the Christian seminaries among the top ten, while the four ordinary secondary schools represented the bottom ten in the second category. Altogether, the ten secondary schools were chosen representing the key characteristics of the total population. The categories of sample respondents and their number from each school add up to 160 of the total population sample. The sample respondent categories included 10 heads of schools, 10 discipline masters or mistresses, 40 teachers and 100 students.

Sampling procedures

Sampling procedures that were employed in this study included purposive sampling, stratified random sampling and simple random sampling.Purposive sampling in this study involved the selection of those participants who portrayed the key characteristics or elements with the potential of yielding the right information. According to Fraenkel and Wallen (2000:112), purposive sampling is an occasion based on previous knowledge of a population and the specific purpose of the research investigators for use in personal judgments to select a sample. In this study the purposive technique was employed to select category of schools, heads of schools and discipline masters or mistresses.

Schools: Ten schools that informed the study were purposively selected following the number of frequencies they appeared in either the first ten (best-performing) positions or the last ten (worst-performing) schools over the 15-year period i.e. from 1992-2007 at interval of three years. Six Christian seminaries were obtained from among 25 top ten (best performing) institutions, where four Christian seminaries that had appeared between five and three times were targeted due to their high frequency and other two were obtained through simple random selection from the rest that had frequented two times. The similar procedure was also used to obtain any four among 71 ordinary secondary schools that constituted the bottom least (worst-performing) schools. The seminaries which have shown the highest frequency in attaining the first ten position are indicated in Table 3.1 and those schools which have the highest frequency in attaining the least ten position are indicated in Table 3.2

Heads of Schools: The heads of schools who are the top leaders (administrators or executors) of all school responsibilities including discipline issues were also purposively selected. The heads of schools being custodians of school discipline by virtue of their offices were assumed to have adequate information on school discipline, formulation and implementation of school policies, rules and regulations of the nation at school level, and on various disciplinary actions in the schools and strategies employed to enhance discipline. There was only one head of school in each school and, therefore, the study dealt with ten respondent heads of schools.Discipline Masters or mistresses: A discipline master or mistress, one in each school, was included in the sample because of their position and responsibilities about discipline. They assist heads of schools in dealing with day-to-day disciplinary issues in their respective schools. They were selected purposively because it was also assumed they had adequate information on school discipline, that is discipline of teachers and students and about implementation of all matters of discipline.

Teachers: Teachers were included in the sample because they had relevant and reliable information about discipline matters in schools. Stratified sampling was employed to select teachers on the basis of their experience in teaching and long service in a particular school. The stay in schools included the categories of 1-3, 3-5 and above five years. These have varying levels of knowledge and involvement in discipline matters over time. After then, a total of four teachers in each school were randomly selected from strata of their teaching experience and stay in a particular school. Finally, one experienced teacher from the four respondent teachers in each school who had stayed in the same school for not less than five years was also selected for interview.

Students: This category of respondents was selected to provide information on the influence of school discipline and academic performance in schools. Students were selected through stratified random sampling on the basis of their stay in the school by including those in the Form Three and Form Four or Form Six. They were selected because they were in the high class levels and it was assumed that they had adequate knowledge and involvement in discipline issues in their respective schools. Simple random sampling was employed to select five students from each class. Therefore, ten students were selected from each school. The researcher wrote on small pieces of paper: “included” and "not included” which were then mixed up. The students were invited each to pick one piece of paper. Those who picked “included” formed the sample of the study.

Data Collection

Data collection refers to the process of obtaining evidence in a systematic way to the research problems. This study used two main sources of data as follows.

Sources of data

Primary Sources of Data: Primary data are original sources from which the researcher directly collects data that have not been previously collected. They are first hand information collected through observations, interviews and questionnaires (Krishnaswami, 2002:197 and Kothari, 2003:95). The study collected primary data from the heads of schools, discipline masters/mistresses, teachers and students through questionnaire, interview and observation.

Secondary Sources of Data: These are sources containing data which have been collected and compiled for other purposes such as readily available compendia and already compiled statements and reports. This type contained published or unpublished reports (Krishnaswami, 2002:199). Secondary data were collected through document search on the disciplinary issues.

Methods of data collection

In this study the following techniques were employed to collect information. These include documentary review, interview, observation and questionnaire.

Documentary review

Document search was used in this study. The method entailed data collection from carefully written official school records or documents. The information collected through the review of documents enabled the researcher to cross-check the consistency of the information collected through the questionnaires and interviews (Borg and Gall, 1993). In the light of this study, document such as punishment record sheets were consulted to obtain the kinds of punishment given, and the written records on number of students selected for some tasks or awards and the number of teachers associated with some events was also obtained. The use of documentary review enabled the researcher to record some information regarding the kinds of misbehaviour and punishment given to the offenders and to obtain some information regarding the general performance as well as individuals (Appendix A).

Interview

Interview is a scheduled set of questions administered through oral or verbal communication in a face to face relationship between a researcher and the respondents. More information and in greater depth can be obtained and it allows flexibility as there is an opportunity to restructure questions (Kothari, 2004:98).In the nature of this study both structured and unstructured interviews were employed to collect rich and deep information on discipline related issues from the heads of schools, discipline masters or mistresses as well as experienced teachers (Appendix B, C and D).

Observation

By the help of observational checklist the researcher observed teaching methods used by teachers during teaching learning activities in the classroom. For instance, how students interacted among themselves or with their teachers and how they behaved in general. Furthermore, the researcher observed the number of physical resources such as libraries, laboratories, teachers’ houses, offices, students’ dormitories and number of classrooms and classroom facilities. The data obtained through observation complemented the data gathered through interviews, questionnaires and documentary review. (Kothari 2004:96) indicates that observation increases the chance for the researcher to obtain a valid and credible picture of the phenomenon being studied. The method thus helps the researcher to have an opportunity to look at what is taking place in the situation. Besides, he argues further that this method tends to eliminate subjectivity and bias in data collection and it gives accurate information relating to what is actually seen in time and place (Appendix E).

Questionnaire

The questionnaire consists of a mixture of open ended and closed-ended questions. Open-ended questions offer more freedom to the respondents to answer the questions while closed ended question items limit the respondents to specificity of the responses for purpose of quantification and approximation of magnitude. In this study questionnaires were administered to both teachers and students for obtaining information concerning their understanding and perceptions of the link between school discipline and academic performance. This method was chosen because a lot of information from a large number of people can be collected within a very short time and it is economical in terms of money and time, for there is a possibility of mailing them. As Kothari (2004:105) maintains, questionnaires are relatively easy by which the researcher can administer the questions and collect a considerable amount of information (Appendix F and G).

Validity and reliability of the study instruments

Since there is no single data collection technique that is by itself sufficient in collecting valid and reliable data, the study used multiple data collection techniques. These procedures refer to the strategy of using several different kinds of data-collection instruments, in which one instrument complements another. The main job of the researcher was to look at the relevance, consistency and validity of the instruments to be administered for ease of elaboration, clarification and proper interpretation. Before the field study, the research instruments were pre-tested at Morogoro secondary school in Morogoro region as it is assumed to have characteristics similar to the rest of other educational institutions intended for study. Correction, modification and adaptation were then effected accordingly so as to suit the purpose of the study. In the field, the researcher increased the reliability of data by clearly explaining the purpose of the study to the respondents and clearing some doubts raised by respondents.

Data analysis procedures

Data analysis is a process that implies editing, coding, classification and tabulation of collected data (Kothari, 2003:122). Since the study involved both qualitative and quantitative data, the data analysis was done both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Qualitative data analysis

The data collected from interviews, open-ended questionnaires and documentary review were subjected to thematic analysis, which was carried out by designed detailed descriptions of the case study and using coding to put themes into categories. Thus, the data collected from the heads of schools, discipline masters or mistresses, students and teachers on the relationship between school discipline and academic performance were coded, quantified and categorised according to the research tasks and their questions. Later on the data were tabulated, and the frequencies and responses calculated as percentages. Some of the respondents’ views and opinions were presented as quotations. These were then interpreted to reveal the influence of school discipline and academic performance in schools.

Quantitative data analysis

The data from the documentary review, structured questionnaires and observation were subjected to quantitative data analysis. The tabulation and calculation of number of frequencies, percentages and graphs were carried out by the help of Statistical Package for Social Science software programme (SPSS).

Ethical issues and considerations

Ethical procedures for conducting research were observed during the process of preparation and conducting field study. Research permits were obtained from the offices of Vice Chancellor- University of Dar es Salaam, Regional Administrative Secretaries of Kilimanjaro, Dodoma, Morogoro, Coast and Kagera Regions, and the District Administrative Secretaries of Moshi, Dodoma Rural, Kondoa, Morogoro Urban, Ulanga, Kibaha and Bukoba Rural.

During the data collection process, informed consent of the respondents was sought, and respondents were assured beforehand of the confidentiality and privacy of the information they would provide. Anonymity of respondents was adhered to when storing and processing data.

The researcher has accordingly acknowledged all scholarly work and data consulted including books, journals, theses, newspapers and field data.

Data presentation, analysis and discussion

Chapter Three dealt with the research design and methods used to collect data to address the problem and the knowledge gap identified in chapters one and two respectively. In this chapter, data presentation, analysis and discussion of research findings are presented in the light of the research tasks articulated in Chapter One. To recapitulate, the research tasks included:

To examine the extent to which school discipline influences academic performance in schools;

To investigate the ways school rules and regulations are formulated and enforced; and

To examine the extent to which the management of the school plays a role to maintain school discipline.

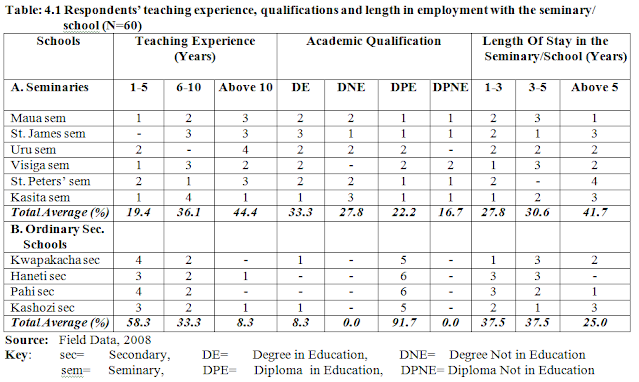

The schools studied were six Christian seminaries and four ordinary secondary schools. The characteristics of the sixty respondent teachers (i.e. ordinary classroom teachers, heads of schools and discipline masters or mistresses) regarding their professional education, length of stay in one’s work station, and experience in teaching were explored. It was the researcher’s contention that their consideration was necessary for discussion on discipline and academic performance in schools. Table 4.1 shows the characteristics of the respondents.

The Extent to which school discipline influences academic performance

The first task of the study was aimed at examining the extent to which school discipline influences academic performance in seminaries and ordinary secondary schools. The information was obtained through interviews to the Rectors, heads of ordinary secondary schools, discipline masters or mistresses, and experienced teachers, through questionnaires to teachers and students, as well as through observation.

Discipline related problems among students and teachers in both school categories

The researcher wanted to explore common discipline related problems among students and teachers in both categories of schools. The findings obtained from heads of schools, discipline masters/mistresses and experienced teachers are as indicated in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2 Teachers’ responses on discipline related problems among teachers and students

Christian seminaries ordinary secondary schools

Common discipline related problems among students

In Christian seminaries the majority of interviewed revealed that the major discipline related problems among students included lateness 12 (66.7%) which was expressed in coming late to school especially after holidays, coming late to class and to church; absconding from some school activities 11 (61.1%) and laziness 15 (83.3%). Lateness reduced time for attending or accomplishing an activity, including some academic and moral teachings which affected performance. Laziness was considered as leading to incomplete work or loss of time while absconding from school meant avoiding classes and some other religious activities without an acceptable reason. Repetition of the same problem was treated as a serious offence that could mar the school atmosphere. For example, repeated lateness was regarded as equivalent to truancy which led to suspension or dismissal from the seminary.

In addition, through the questionnaires administered to teachers, the findings revealed that lack of total commitment in Christian seminaries was considered as a disciplinary problem as indicated by 18 (75.0%) respondents. Lack of teachers’ as well as students’ commitment to Christian principles and philosophy had been identified as one critical factor that could affect school discipline, and hence poor performance. Generally, the interviewed respondents asserted that there were no such rude behaviours amounting to violent or criminal misconduct in their seminaries. However, the disciplinary problems already explained, in their view, still negatively affected the learning environment.

In ordinary secondary schools some of the findings were similar to those explained by their counterparts. However, there were areas of difference especially in degree, type and/or frequencies. Problems similar to those in seminaries included lateness 12 (100), laziness 9 (75.0%) and absconding 10 (83.3%). However, it was explained that these problems were more chronic when compared with seminaries. Furthermore, the type of disciplinary problems indicated that truancy 11 (91.7%), smoking marijuana 10 (83.3%), absenteeism 10 (83.3%) and abusive language 9 (75.0%) were common in ordinary secondary schools, which lacked in Christian seminaries. The respondents explained that these misbehaviours were poisoning the learning atmosphere in their schools. A discipline mistress at Kwapakacha Secondary School, in Kondoa District, explained:

In my school some of the students attend school willingly while others do not come to school regularly because of the negative influences in their lives including problems with families, mob psychology and or fear of punishment. Many students who miss school during regular hours are found committing some other crimes including smoking of marijuana (29- 09-2008).

The findings suggest that truancy was the most powerful predictor of delinquent behaviour. It was explained that students who frequently missed schools also fell behind their peers in classroom work performance and finally dropped out. Smoking marijuana as experienced in Kwapakacha secondary school was practiced by students who absented themselves and hid in places (called ‘vijiweni’) during class hours. These places sold tobacco, marijuana and other drugs. As this affected their brains they would not behave well nor concentrate on study tasks, which in turn led to poor performance.

Common discipline related problems among teachers

Most subjects who were interviewed in Christian seminaries maintained that there were hardly any discipline related problems among teachers. What was seen was that some teachers in Christian seminaries tended to obey seminary rules and regulations simply because the environment of the seminary forced them to do so, and that obedience did not emanate from their hearts. In Christian seminaries obedience which was strictly emphasised was that of the level emphasised through their Christian faith (Philippians 2:8), something that the less committed people could not afford. Obedience in seminaries sometimes meant a teacher being forced to obey some of the unfavourable seminary rules and regulations without questioning, which bred inner dissatisfaction.

As regards ordinary secondary schools all interviewed respondents maintained that acts of discipline among teachers resembled in nature those committed by their students. Specific acts by teachers included: absenting themselves from classes with no permission and absconding from school during class hours, which led to missing lessons. Frequency in committing these led to friction between the teachers concerned and the administration, which in turn affected performance. Unlike Christian seminaries it was found out that absenteeism 10 (83.3%) of teachers in ordinary secondary schools was common, as some teachers were frequently away from work during class hours for reasons not known or accepted by the school authority, such as attending “paid” tuition classes elsewhere and other private business. Another problem, to a degree related to absenteeism, was drunkenness 8 (66.75) that led to poor attendance to school activities.

Reasons for violation of school rules and regulations among teachers and students

In this particular sub-task, through interviews with experienced teachers, discipline masters or mistresses and heads of schools and through questionnaires administered to teachers and students, the respondents were asked to give reasons that led both teachers and their students to violate school rules and regulations. Most of the reasons were common to both teachers and students while some were exclusive to students and others to teachers. On other hand, despite that most of the reasons were to be found in both categories of schools, they differed in their type and degree. The findings revealed the following reasons that could lead to violation of school rules and regulations:

Ignorance of school rules and regulations

In Christian seminaries it was asserted that when teachers were not well informed about the terms and conditions of their employment and about the rules and regulations in their school, there was a possibility to infringe upon them. One teacher from Maua Seminary, in Moshi Rural District, asserted that:

In our seminary this is not a big issue since teachers are informed about school rules and regulations before signing their employment contract and during orientation where teachers are informed about school affairs. (24-09-2009).

In ordinary secondary schools it was revealed that sometimes misconduct occurred simply because teachers and students did not know how to act appropriately because they were ill informed about school rules and regulations. Interviews revealed that in all four ordinary secondary schools the mode of informing about rules and regulations was practiced differently from that in the Christian seminaries where teachers had to pass through each of the rules before finally accepting or rejecting the employment contract. It was also found out that the same situation faced students when they were not adequately informed about school rules. In this context inadequate information about school rules led to deviant behaviours that in turn could lead to poor performance.

Poor Motivation

Poor motivation lowered teachers’ morale due to unsatisfactory working conditions. This was more common especially in public schools where teachers lacked houses, and were not paid adequate money to be able to rent good houses. Lack of adequate school facilities like libraries, laboratories and late delivery of services such as delayed salary and other allowances also increased the dissatisfaction among teachers. The respondents in Christian seminaries, however, reported that the problem was not as serious as in normal government schools. For example in St. Peter’s Seminary the only housing problem was that two lay teachers had to share a house which in their view it could lead to some misunderstandings which by seminary standards they were considered a breaching of social as well as Christian faith-based values. Furthermore, observation revealed that all Christian seminaries provided boarding to students as well as housing facilities to all teachers. Unlike Christian seminaries, most ordinary secondary schools lacked housing facilities for their teachers which led them to rent rooms or houses outside the school compound. One teacher from Haneti Secondary School, in Dodoma Rural District, had this to say:

Secondary school teachers have been demoralized and frustrated by their employer because they are either lowly paid, they live in poor housing conditions, resulting in low morale, which in turn makes teachers concentrate less on students’ welfare (31-09-2008).

The quotation above confirms the view by Mwaipaja (2000:184) who maintained that low salaries, poor medical services, lack of transport facilities and a poor school environment make teachers less motivated to perform their expected responsibilities. The level of efficiency of a teacher who enjoys residence facilities built around the school is expected and has been observed to be higher than for teachers live far away from the school. It was observed that in all ordinary secondary schools there were delays among teachers in attending the first class period in the morning as most teachers were late. This reduced the total time a teacher needed to be in contact with students. More information on the availability of school physical resources on both Christian seminaries and ordinary secondary schools is shown on Table 4.3

Overcrowded classesIt was found out that in Christian seminaries all classes were small and therefore manageable. Commenting on this, Kung’alo (2000:193) argues that although the seminary can accommodate up to 500 students, the Bishops decided to aim at a smaller number which could produce good results. They insisted on quality rather than quantity, as overcrowded classes led to the failure of the teacher to monitor the class and to pay attention to individual students.

On the other hand, the study found out that some of the ordinary secondary schools, for example Kwapakacha Secondary School, had a large number of students registered up to 70 per stream. The respondents asserted that overcrowding in classrooms affected efficiency and effectiveness of teaching and supervision thus affecting teachers’ morale. It also had an effect on both the ability of the teacher to help individual students and the frequency of assigning homework. For example, while teachers in Kasita Seminary indicated that they gave assignments on the weekends, those in Kwapakacha Secondary school did not practice this. A teacher at Kwapakacha, in Kondoa District, observed:

Where classes are typically more than 50 students in one stream, maintaining order in the classroom can divert the teacher from instruction, leaving little opportunity for concentration and focus on what is to be taught (29-09-2008).

This problem might encourage misconduct as a result of distracted teacher attention and actual overwhelming of the teacher, who could easily overlook his or her duty of rectifying students’ misbehaviours, finally affecting academic performance.

Shortage of teachers

In Christian seminaries it was reported that currently they had an adequate complement of teachers, except Uru Seminary where Vice Rector indicated shortage of two teachers. As a temporary measure the seminary hired part-time teachers from other schools. On the other hand, in all ordinary secondary schools the number of teachers was too small to allow for effective teaching and learning processes. With comparatively large class sizes, all the secondary schools under study experienced a lot of pressure, with teachers carrying extraordinarily big workloads and the schools thus apparently understaffed. Teaching and knowledge delivery as a whole was highly constrained. A teacher from Pahi Secondary School, in Kondoa District, asserted that:

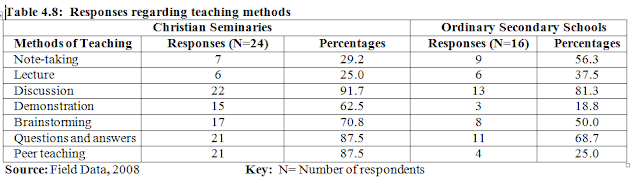

Due to acute shortage of teachers in schools, we teachers resort to the lecture method, which reduces teacher-student interaction. We hardly mark students’ exercises and, as such, suppress student curiosity (02-10-2008).

The ratio of students to the teachers in both Christian seminaries and ordinary secondary schools as given by heads of schools and the Rectors is summarised in Table 4.4 below.

The teacher-student ratio in ordinary secondary schools ranged from 1:51-1:56 with an average level 1:54. This ratio was higher when compared with Christian seminaries, in which the teacher-student ratio ranged from 1:11-1:19 with an average ratio of 1:15, which was far below the national teacher-student ratio of 1:40. Following the shortage of teachers in ordinary secondary schools some responsibilities were either not fulfilled or poorly executed. For example, in Haneti Secondary School one teacher was a supervisor of school cleanliness, a students’ counsellor, a class teacher and a head of department, apart from having a teaching load of 35 periods per week. As a result, some of her lessons went missing when she had to attend to other duties. On the other hand, in Christian seminaries there was an opportunity for teachers to attend to every individual student fully in and out of class, it being easy for them to control students’ discipline and orient them towards academic affairs. This was not well fulfilled by their counterparts in ordinary secondary schools where, in some instances, some subjects were not taught because the school had no specialised teachers for them, as was the case of physics at Pahi Secondary School. This affected academic performance and provoked dissatisfaction from students.

Inconsistent use of punishments

The seminaries claimed that when executing disciplinary actions, it was consistently and fairly applied to students or teachers depending on the nature of the offence regardless of an individuals’ other positions or ranks. The study revealed that, unlike the situation in Christian seminaries, some of misbehaviours in ordinary secondary schools were a result of inconsistency in the use of disciplinary action towards the offenders. One teacher from Pahi Secondary School had this in comment:

Unfair and inconsistent enforcement of school rules makes students lose faith in rules. If a teacher ignores breaking of a rule one day and comes down hard on the same the next day, one will not be seen as being consistent, therefore one is likely to lose respect and breaking of the rule will probably increase (02-10-2008).

The above view predicted that consistency and fairness in executing school rules were essential for effective classroom or school management. Variations in the way similar offences were dealt with in a school would likely cause discontent among teachers and students thereby negatively affect academic performance.

Leadership style

Most teachers in Christian seminaries indicated that the style of leadership was more or less characterised by rigidity of rules and uniform application in executing such rules. There were less bureaucratic procedures in reaching and implementing leadership decisions. For example, in Christian seminaries the Rector has the power to involve or not involve the discipline committee in expelling or terminating a student who has committed an offence. In this case the seminary board is only informed. Thus in seminaries there are elements of dictatorial leadership. As such any deviance was responded to immediately and deviations from the norm were also regarded as going against the principles of Christian faith. On the other hand, the leadership style in ordinary secondary schools was more lax and decision making was more bureaucratic involving more stages and people, which gave loopholes for some deviant behaviour that affected academic performance in general. For instance, once a student is found guilty, the school administration would only suspend the student and later on inform the board for further actions.

However, talking about issues on motivation, overcrowding, shortage of teachers and delaying of services such as of salaries involved the level of the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training that was beyond the jurisdiction of the school and was bureaucratic in nature. Unlike the situation in ordinary secondary schools, all factors that could bring disciplinary problems in Christian seminaries were within control of the institution and it was less bureaucratic in dealing with them.

One further factor mentioned by teachers in connection with violation of school rules and regulations was irresponsibility on the part of parents. In Christian seminaries 14 (58.3%) of teachers and 15 (93.8%) in ordinary secondary schools pointed out that a sense of irresponsibility on the part of parents could be one possible reason for students breaking school rules and regulations. It was pointed out that some parents did not cooperate fully in the disciplining and following-up of academic progress of their children. In seminaries it was found that screening of the candidates for joining their schools involved adequate knowledge on and appreciation or acceptance of their parents’ conduct whereby only children of parents who were regarded as socially and religiously responsible were selected. Carefree parents, as was reported in connection with ordinary secondary schools, bred a fertile ground for their children to become lax in school matters, thus affecting their discipline and ultimately lowering their performance levels.

The researcher was interested in capturing students’ knowledge and views concerning discipline and performance. Their responses are indicated in Table 4.5

From the table it can be discerned that students in both categories of schools had a similar degree of awareness on issues relating to disciplinary problems. Coming to school late, the use of abusive language, cheating during examinations and missing classes were seen as leading in the way they were regarded as seriously affecting discipline. However, while in most cases they were not frequently committed in Christian seminaries, which are boarding schools, these problems were more prevalent in ordinary secondary schools, which were all day schools. As students went to school daily by bus or on foot, they often arrived late, which led to their missing some parts of classes and being punished. The interviews held with experienced teachers revealed that cheating during examinations and plagiarism were common in ordinary secondary schools while in seminaries lying, cheating, copying or plagiarizing were treated as ‘intolerable’ disciplinary offences which led to instant dismissal. The totality of these problems often affected performance of individual students.When students were asked about the right behaviour with respect to school rules and regulations, their responses were as shown in Table 4.6.

Students in Christian seminaries indicated to be more sensitive about the rules as expressed in the higher degree of their “agree” responses, reflecting the nature of how they were sensitised and affected by such rules. As with students in ordinary secondary schools some of the students’ answers on smoking and drinking alcohol proved the contradiction between rules at the home (where they resided) and rules at school (where they spent day hours). At home they were allowed to drink alcohol and they socialized with smokers, which attracted them to attempt such practices. This could affect their health and their brain, thus affecting their concentration on academic affairs.

Furthermore, students were asked to give their views on what was actually taking place in their respective schools. Table 4.7 summarises their views.

Through students’ questionnaires on the kind of actions done by their teachers that could lead to disciplinary problems, degrees of differences were found among the two categories of schools. While the majority of both categories agreed that teachers in their schools were strict, 20 (50.6%) of students in ordinary secondary schools indicated that some teachers did not teach, against 15 (25.0%) by their counterparts. 59 (98.3%) of students in Christian seminaries and 26 (65.0%) students in ordinary secondary indicated that teachers helped their students to solve problems. Taking the discrepancy to be at the level of academic performance between the two categories, it could be said that some teachers in ordinary secondary schools were also preoccupied with attending to problems other than academic ones as many students indicated that some teachers did not teach. As with Christian seminaries, offering services was one of their vocational commitments which motivated them to attend to their students.The ways school rules and regulations are formulated and enforced in schools

Task two of the study sought to investigate the ways school rules and regulations were formulated and enforced. Interviews were held with heads of schools, discipline masters or mistresses and experienced teachers, while questionnaires were administered to teachers and documents relating to the two categories of schools were also reviewed.

Involvement in the formulation of school rules and regulations in schools

Respondents in Christian seminaries asserted that seminary rules and regulations were formulated on the basis of both government educational policy and their Christian faith. Some rules in Christian seminaries were direct from the Ministry of Education. For example, Maua Seminary rules on school uniform (Appendix H No.4D) concurred with those laid down by the Ministry of Education in chapter 6E in “Kiongozi cha Mkuu wa Shule ya Sekondari Tanzania” (MOEC, 1997). Other seminary rules and regulations were more or less modified to fit the local environment and the aims of seminaries. The Vice-Rector at Visiga Seminary, in Kibaha District, explained:

The ways to formulate and implement seminary rules and regulations differ between seminaries, either Diocesan or Congregation. Generally, the formulation of rules and regulations in Christian seminaries is hierarchical from the top Board of Bishops to the Members of Congregations. Then follows the Board of Vocation Directors, who constantly communicates with the Rector of the seminary in carrying out the deliberations of the two boards. The Rector, who is also the Secretary of the Board of Directors and the Principal Executive Officer, supervises staff members consisting of priests, sisters and the lay teachers. On the part of students leaders there are prefects and class monitors (19-09-2008).

The findings revealed that the formulation of seminary rules and regulations was a two way system. On the one hand, formulating rules emanated from the normal policies of the Ministry concerned with education. On the other hand it was integrated with Christian faith. This is in line with what was stipulated in “Sera ya Elimu ya Baraza la Maaskofu Katoliki Tanzania” (2005:4-12). The Christian faith-based policies were laid down by a Board of Bishops and the members of Congregation (who are the owners of the seminaries or policy makers), and the rules were executed by the Rectors and teaching staff (implementers of rules and regulations). There was Vocation director position that formed the link between the policy makers and implementers, and the position’s duty included advising both parties on the proper character formation of the seminarians. During execution of the rules by the seminary management, some rules were fixed by the higher authority and could not be modified e.g. daily administering and attending of the religious Mass, while others depended on the position of the individual seminary e.g. permission to go outing. With regard to students, rules were handed to them and they could only advise on the minor implications of the rules whose modification was within the management’s jurisdiction. The interconnectedness indicated above within the Christian seminary structure seems to have resulted into an observable link between conducive teaching, a generally tranquil learning environment in seminaries and a reign of discipline.

In ordinary secondary schools the findings on the formulation of school rules and regulations revealed a similar picture of rules being formulated hierarchically. At the top there is the Ministry of Education and the school Board (owners of the school) down to the school management (implementers). Figures 4.1 and 4.2 show the organizational structure of both Christian seminaries and ordinary secondary schools, respectively.

Through questionnaires, the findings indicated that slightly over a half of the teachers i.e. 9 (56.3%) in ordinary secondary schools and a similar proportion, i.e. 14 (58.3%) of teachers in Christian seminaries were involved in the formulation of school rules and regulations. It was also found out that the category of teachers who agreed that they were involved had worked in their schools for not less than five years. This might mean that teachers at one stage or another got involved in the formulation process to establish the rules. What students mostly did was to implement after the formulation process had been accomplished.Ways in which School Rules and Regulations Were Made Clear and Agreeable to Both Teachers and Students

Through interview with heads of schools, discipline masters or mistresses and experienced teachers, the researcher wanted to find out the ways school rules and regulations were made clear and agreeable to teachers and students. The findings are presented and discussed as hereunder.

Use of a School Rules Handbook: Such handbooks spelled out the rules of conduct, the reasons for the rules and also the consequences of not following these rules. In Christian seminaries all respondents asserted that handbooks were given to newly admitted students and to teachers during the process of formalising the contract. On the contrary, their counterparts in ordinary secondary schools claimed that they were not given such handbooks by their employers.

Staff Meetings: All respondents in all schools explained that regular staff meetings were held two /three times per term, before opening the school, between the term and at the end for assessment and review. The Rector, at Maua Seminary, in Moshi Rural District, explained thus:

In the meeting staff members get informed and reminded of the school rules and regulations in addition to what is given before a contract is signed. Often new rules are made or old ones are modified as the situation dictates, and this should be communicated to the relevant people promptly (24-09-2008).

It was apparent therefore, that staff meetings in schools helped to keep all members of staff well informed and involved in schools’ undertakings/events.

Orientation and Induction Course: In seminaries it was explained that before the official opening of the academic year, both the newly employed teachers and newly admitted students had to go through an orientation course which might take one week for teachers and two weeks for students. During the orientation session, copies of rules and regulations were given to both staff and students and they were made clear and interpreted. On this Okumbe (1998:119) maintains that educational managers must ensure that all staff members and students are informed about rules and regulations of the school and the consequences of breaking them. In ordinary secondary schools it was revealed that all newcomer students had to go through an orientation course for two weeks, but newly employed teachers were sometimes not instantly informed about the rules informing teachers’ conduct.

School Baraza: During these meetings school rules were explained and students could ask questions to or seek clarifications from the authority on the issues that raised their doubts. In both categories of schools the findings disclosed that holding of the school baraza ranged from two to three times per term. In Christian seminaries the study found that there were students-Rector meetings that ranged from once a week to once a month in addition to the students’ Baraza. For instance, Uru, St. Peters’ and St. James held their meetings with their Rectors once a week. The variations in the timing of meetings was meant to give chance to other position leaders e.g. spiritual directors, academic and discipline masters to meet with the students and discuss various issues on spiritual, academic and discipline life. This was quite different from ordinary secondary schools where there were no scheduled students-head meetings but only the school baraza. In this situation, the frequency of students to interact with the authority on various issues varied.