Classical socio ethical theories (The principles of moral action)

In normative ethics, we try to arrive, by rational means, at a set of acceptable criteria which will enable us to decide why any given action is ‘right’ or any particular person is called ‘good’. In ethics, normative theories propose some principle or principles for distinguishing right actions from wrong actions. These theories can, for convenience, be divided into consequentialist and non-consequentialist approaches. In this study we shall deal with three of these theories: Consequentialist, Deontologist and Virtue Ethic theories.

Teleological Theory (consequentialism)

The word teleology comes from the Greek word “telos”, meaning “end” or “final results”. It maintains that moral judgments are based entirely on the effects produced by an action. An action is considered right or wrong in relation to its consequences. This view appeals to our common sense. Often, when considering a course of action, we ask: ‘Will this hurt me?’ or ‘Will this hurt others?’ Thinking like this is thinking teleological: whether we do something or not is determined by what we think the consequences will be; whether we think they will be good or bad. Inevitably, of course, people have different opinions about whether a particular result is good or bad, and this accounts for the great variety of teleological or consequentialist theories.

Thus, an act is right if and only if it will probably produce, or is intended to produce at least as great a balance of good over evil as any available alternative; an act is wrong if and only if it does not do so. An act ought to be done if and only if it will probably produce, or is intended to produce a greater balance of good over evil than any available alternative. For a teleologist, the moral quality or value of actions, persons, or traits of character is dependent on the comparative non moral value of what they bring about or try to bring about. In order to know whether something is right, ought to be done , or is morally good, one must know what is good in the non moral sense and whether the thing in question promotes or is intended to promote what is good in this sense.

Some consequentialists have identified good with pleasure and evil with pain, and concluding that the right course or rule of action is that which produces at least as great a balance of pleasure over pain as any vice versa.

Thus, in order to make correct moral choices, we have to have some understanding of what will result from our choices. When we make choices which result in the correct consequences, then we are acting morally; when we make choices which result in the incorrect consequences then we are acting immorally. Therefore, according to this theory, what is ethically right is determined through an evaluative process. It maintains and advocates the general rule of actions which says, “Choose the action that is likely to produce the greatest good for the greatest number”.

The two major consequentialist theories

The two major consequentialist theories are egoism and utilitarianism. They are distinguished by their answers to the question that arises from this theory, i.e. consequences for whom? Should one consider consequences only for oneself?

a) Egoism

The view that associates morality with self interest is referred to as egoism. Egoism contends that an act is morally right if and only if it best promotes the individual’s long-term interests. Egoists use their long term advantage as the standard for measuring an action’s rightness. If an action produces, will probably produce, or is intended to produce for the individual a greater ratio of good to evil in the long run than any other alternative, then that action is right to perform. The individual should take that course to be moral.

Moral philosophers distinguish between two kinds of egoism: personal and impersonal. Personal egoists claim they should pursue their own best long-term interests, but they do not say what others should do. Impersonal egoists claim that everyone should follow his or her best long term interests.

Egoists seek to guide themselves by their own interests, regardless of the issue of circumstances.

Ethical egoism ignores blatant wrongs (offensive behaviour), they reduce everything to the standard of best long term self interest, egoism takes no stand against seemingly outrageous acts like stealing, murder, racial and sexual discrimination, false advertising, etc. All such actions are morally neutral until the test of self interest is applied.

b) Utilitarianism

This is the moral doctrine that we should always act to produce the greatest possible balance of good over bad for everyone affected by our action. By “good”, utilitarians understand happiness or pleasure. Thus, they answer the question “what makes a moral act right?” by asserting: the greatest happiness of all. Jeremy Bentham (1748 - 1832) and John Stuart Mill (1806 - 1873) were the first to develop the theory explicitly and in detail. Both were philosophers with interest in legal and social reform. They used the utilitarian standard to evaluate and criticize the social political institutions of their day. For example, the prison system. As a result, utilitarianism has long been associated with social improvement.

Bentham argued for the utilitarian principle that actions are right if they promote the greatest human welfare, wrong if they do not. For Mill, the utility principle allows consideration of the relative quality of pleasure and pain. Both identified pleasure and happiness and considered pleasure the ultimate value. In this sense they are hedonists: pleasure, in their view, is the one thing that is intrinsically good or worthwhile. Anything is good because it brings about pleasure (or happiness), directly or indirectly. Take education, for example. The learning process itself might be pleasurable to us; reflecting on or working with what we have learned might bring satisfaction at some later time; or by making possible a career and life that we could not have had otherwise, education might bring us happiness indirectly.

The problem with teleological or utilitarianism is the impossibility to compare utility on the interpersonal level. If the right action is what produce the net good for me, then there is a possibility of being so uncaring, unconcerned to the other person, especially if he or she is a stumbling block to my maximizing of the good. For utilitarian, the end justifies the means; that is, the end, which is maximizing the net good, determines the means an individual will use to attain his or her end. As history has taught us this can be really dangerous. If, for instance, the rich want to maintain getting exorbitant profits, they will go to all limits, corruption, evading taxes and dubious business deals, so as to maximize what they see as their net good.

Deontological Theory (Kant’s Ethics)

The word deontology comes from the Greek roots “deon”, which means “duty”, and “logos”, which means “science”. Thus, deontology is the “science of duty.” Deontology is an approach to ethics that determines goodness or rightness from examining acts, or the intentions of the person doing the act, as it adheres to rules and duties. This contrast to consequentialism, in which rightness is based on the consequences of an act, and not the act by itself. In deontology, an act may be considered right even if the act produces a bad consequence, if it follows the rule that “one should do unto others as they would have done unto the m”, and even if the person who does the act lacks virtue and had a bad intention in doing the act. According to deontology, we have a duty to act in a way that does those things that are inherently good as acts, or follow an objectively obligatory rule. For deontologists, the ends or consequences of our actions are not important, and our intentions important.

Kant sought moral principles that do not rest on contingencies and that define actions as inherently right or wrong apart from any particular circumstances. Kant’s ethics contends that we do not have to know everything about the likely results of, say, my telling a lie to my boss in order to know that it is immoral. The basis of obligation must be sought in nature, not in the circumstances of the world. An act is to be judged as good or bad depending on the person’s intentions. Kant believed that the goodness of things or an act such as self-control, courage, happiness, and so on, depends on the will that make use of them.

Only when we act from duty does our action have moral worth. When we act only out of feeling, inclination, or self interest, our actions although they may be otherwise identical with ones that spring from the sense of duty have no true moral worth. For example, following up a customer and giving him or her back the change which she had left back, with apologies, you may not have necessarily acted from good will but may be from the desire to promote business or to avoid legal entanglement. According to Kant, if you do not will the action from a sense of your duty to be fair and honest, your action does not have true moral worth. Actions have true moral worth when they spring from recognition of duty and a choice to discharge it.

According to this theory, when we fulfil our duties, obligations and responsibilities, we are behaving morally and when we fail to fulfil them we are behaving immorally. Typically in any deontological system, our duties, rules, and obligations are determined by God. Being moral is thus a matter of obeying God.

Immanuel Kant’s theory of ethics is considered deontological for several different reasons.

First, Kant argues that to act in the morally right way, people must act from duty. Second, Kant argued that it was not the consequences of actions that make them right or wrong but the motives of the person who carries out the action.

Immanuel Kant insisted that what makes an act right or wrong cannot be its consequences which are often entirely out of our hands and a matter of luck but the principle or maxim which guides the action. There are certain obligations and duties that must be respected even if doing so does not produce the desired results or consequences. The heart of Kant’s ethics is, “duty for duty’s sake”, not for the sake of the consequences.

Deontological moral systems typically stress the reasons why certain actions are performed. Simply following the correct moral rules is often not sufficient; instead, we have to have the correct motivations. This might allow a person to not be considered immoral even though they have broken a moral rule, but only so long as they were motivated to adhere to some correct moral duty. E.g. one may do something apparently right with a wrong intention or one may do something bad or wrong with a good intention. Our duties and obligations should be fulfilled regardless of one’s desire.

The questions that can be raised for this theory are: Is it the motive of duty that gives it its morality?

Is it only her sense of duty and not her love for her child that gives morality to a mother’s devotion?

Is it only cold obligation and not large-hearted generosity that makes relief of the poor a moral act? Certainly a sense of duty will be present in such cases, but love and generosity are always esteemed as higher motives than mere duty and give the act a greater moral worth. We fall back on duty only when other motives fail. How could Kant explain heroic acts, such as giving one’s life for one’s friend? These acts are always thought the noblest and best precisely because they go beyond the call of duty.

Different kinds of deontological theories

Act deontological theories

These maintain that the basic judgments of obligation are all purely particular ones like “In this situation I should do so and so,” and that general ones like “We ought always to keep our promises”, are unavailable, useless, or at best derivative from particular judgments. Extreme act deontologists maintain that we can and must see or somehow decide separately in each particular situation what is right or obligatory thing to do, without appealing to any rules and also without looking to see what will promote the greatest balance of good over evil for oneself or the world. Such a view was held by E. F. Carrit and by H. A. Pichard; and was at least suggested by Aristotle when he said that in determining what the golden mean is “the decision rests with perception.”

Rule deontological theories

They hold that the standard of right and wrong consists of one or more rules – either fairly concrete ones like “We ought always to tell the truth” or abstract ones like “It cannot be right for A to treat B in a manner which it would be wrong for B to treat A”. They insist that these rules are valid independently of whether or not they promote the good. In fact, they assert that judgments about what to do in particular cases are always to be determined by in the light of these rules as they were by Socrates in the Apology and Crito. Examples of rule deontologists: Samuel Clarke, Richard price, Immanuel Kant, etc.

Complementarity of the deontological and teleological theories

Purely deontological and purely teleological theories are ideal types and cannot stand singly to determine the foundation of moral norms. In order to arrive at a concrete basis of the moral norm, both deontological theories, including information on the nature of the laws and mechanisms of the act, and teleological theories, that is the purpose, object and goal of the act must be considered.

The teleological theory should not be understood as systems that determine the morality of an action so exclusively by consequences that no room is left for deontological considerations. Such considerations remain essential and indispensable. So, deontological and teleological considerations stand in need of each other. They are not mutually exclusive, but rather complementary to each other in order to reach a moral basis of the evil or goodness of action.

Virtue ethics theory

Throughout its history morality has been concerned about the cultivation of certain dispositions, or traits, among which are “character” and such “virtues” as honesty, kindness, conscientiousness, and so on.

What are virtues?

Virtues are dispositions or traits that are not wholly innate; they must all be acquired, at least in part, by teaching and practice, or, perhaps, by grace. They are also traits of “character”, rather than traits of “personality” like charm or shyness. They all involve a tendency to do certain kinds of action in certain kinds of situations, not just to think or feel in certain ways. They are not just abilities or skills, like intelligence or carpentry, which one may have without using.

Virtues are qualities of excellence by which man is rendered more perfect. For Marxists, virtue is the courage to revolt against the capitalists or the ruling classes. Existentialists hold that authenticity or the ability to take risk and to be individual, or to self-actualize is the true and real virtue.

Virtue is twofold, partly intellectual and partly moral, and intellectual virtue is originated and fostered mainly by teaching; it demands therefore experience and time. Moral virtue on the other hand is the outcome of habit. From this fact it is clear that moral virtue is not implanted in us by nature; for nothing that exists by nature can be transformed by habit. It is neither by nature then nor in defiance of nature that virtues grow in us. Nature gives us the capacity to receive them, and that capacity is perfected by habit.

In fact, it has been suggested that morality is or should be conceived as primarily concerned, not with rules or principles as we have been supposing so far, but with the cultivation of such dispositions or traits of character. Plato and Aristotle seem to conceive of morality in this way, for they talk mainly in terms of virtues and virtuous, rather than in terms of what is right or obligatory.

Virtue based ethical theories place much less emphasis on which rules people should follow and instead focus on helping people develop good character traits, such as kindness and generosity.

These character traits will, in turn, allow a person to make the correct decisions later on in life.

The actions of virtuous people stem from a respect and concern for the well-being of themselves and others. Compassion, courage, generosity, loyalty and honesty are good examples of virtues.

Because virtuous people are motivated to act in ways that benefit society, the cultivation of a virtuous character is an important aspect of social ethics. For example, a generous person is more likely to act in ways that benefit those who are least well off in society. Virtues should be learned, acquired, practiced and personalized right from childhood. Thus goes the saying, “charity begins at home”. Virtue in general is a synonym for morality.

Virtue theorists also emphasize the need for people to learn how to break bad habits of character, like greed or anger. These are called vices and stand in the way of becoming a good person. Virtue ethics give a human person the proper direction in his behaviour or actions.

However, to avoid confusion it is necessary to notice that we must distinguish between virtues and principles of duty like “We ought to promote the good” and “We ought to treat people equally.” A virtue is not a principle of this kind; it is a disposition, habit, quality, or trait of the person, which an individual either has or seeks to have. For example, we can speak of the principle of beneficence and the virtue of benevolence to mark the difference, in the case of justice; we can also speak of the principle of equal treatment with the virtue/trait to treat people equally.

Cardinal virtues

By a set of cardinal virtues is meant a set of virtues such that (a) they cannot be derived from one another and (b) all other moral virtues can be derived from or shown to be forms of them. Plato and other Greeks thought there were four cardinal virtues in this sense: wisdom, courage, temperance, and justice. Christianity is traditionally regarded as having seven cardinal virtues: three “theological” virtues - faith, hope, and love; and four “human” virtues prudence, fortitude, temperance, and justice. This was essentially St. Thomas Aquinas’ view, however, many moralists, among them Schopenhauer, have taken benevolence and justice to be the cardinal moral virtues since the other moral virtues - love, courage, temperance, honesty, gratitude, and considerateness can be derived from these two.

Virtues and the mean

It appears then that virtue is a kind of mean because it aims at the mean. Virtues are destroyed by excess and deficiency but preserved by the mean. Too much or too little meat and drink is fatal to health, whereas a suitable amount produces, increases and sustains health. It is the same with temperance, courage, and other moral virtues. A person who avoids and is afraid of everything and faces nothing becomes a coward; a person who is not afraid of anything but is ready to face everything becomes foolhardy. Similarly, he who enjoys every pleasure and abstains from none is licentious; he who refuses all pleasures like a boor (ill-mannered person or insensitive) is an insensible sort of person.

According to Aristotle most virtues entail finding the mean between excess and deficiency. Aristotle’s theory of virtue is this: a virtue is neither too much nor too little, “a mean between the extremes”. It is a kind of moderation and this is cultivated by habitually practicing moderation.

Aristotle was not advising us to take a moderate position on moral issues. The doctrine of the mean is meant to apply to virtues, not to our position on social issues. By suggesting that we seek the mean, Aristotle was not referring to being lukewarm but to seek what is reasonable.

Principles of social ethics

The factors of morality

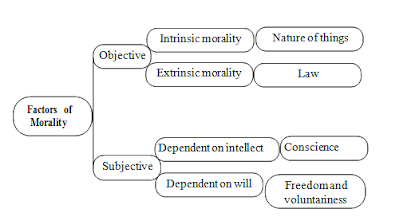

The factors of morality are of two classes, namely objective factors and subjective factors. These factors of morality can be briefly summarized by the following diagram:

The objective factors constitute the source of objective morality of an act, and they are independent of the acting subject. Objective factors of morality are not produced or sanctioned by the individual who acts. They can be intrinsic or extrinsic.

Objective intrinsic morality

What is objective intrinsic morality? Objective intrinsic morality, means that there are moral principles which are objective (accepted by all people), which are intrinsic (which do not derive their morality from any outside factors(s) but from within the act themselves). In other words, they are intrinsic when they depend upon the nature of a given action; when they are the source of the morality an act possesses by its own nature. For example, the intentional poisoning of another person’s food to kill him or her is intrinsically bad in itself. The nature of the act, that is, killing an innocent person intentionally, makes the act to be bad without or independent of what the person who does it believes, unless one is a sadist, sickness is something bad to a person’s health. Health is something good to all. All acts that inflict or can lead to sickness are, thus, bad in themselves; and conversely all acts that promote health are good.

Does an objective intrinsic morality exist? Yes, there are things which are intrinsically good (e.g., life, truth, wisdom, health, friendship, love etc…) and there are others which are intrinsically bad (sickness, death, deception, ignorance, foolishness, etc.). Accordingly, it is that the activities pursuing those things enjoy an objective intrinsic morality, that is, they are either good or bad in themselves.

What makes killing the innocent evil, and obeying the legitimate authority good? A traditional answer is: the objective intrinsic morality of an action is its conformity or non conformity with the proper order of things. Such proper order is determined by the complete physical essence of the elements that make up that act.

The proper order of things means the nature of things. That is, each and every thing has its own uniqueness and laws or principles which govern its existence and activity. For example inorganic matter such as rocks and minerals do not have life in them, yet they respond to the laws of physics.

When you throw a stone in the air, it will obey Newton’s Universal Law of gravitation, by falling down. Living beings, plants, animals and humans – likewise follow the laws of their nature.

Complete physical essence means the actual nature which things have, not in abstract, but in a given concrete situation (example: A man has killed another man. This proposition is abstract. Mr. X is a soldier and in battle he has killed an enemy. This proposition is concrete).

In a more formal language we can say that objective intrinsic morality is the conformity or not of an action with the laws of beings. It is possible to use the “self” or “things” according to or against their nature. For instance, food and wine or beer can be used for nourishment and in this case they are good; yet, if one use them for intoxication, they become bad.

Objective extrinsic morality

They are extrinsic when they do not belong to the nature of the action but they come from other sources; hence, they are external modifiers of the morality of an action. They are the laws which determine the morality an action possesses insofar as it is the object of a command or a prohibition, for example, the laws which govern a country. Let us take an instance of the traffic law that says every driver should slow down or stop at “zebra crossing”. One driver decides to drive at 100km/h, not slowing down at the Zebra crossing. He knocks down a man who later dies in hospital while undergoing treatment. A driver is arrested, convicted and sentenced for life imprisonment, having being charged with careless driving resulting in the death of the boy. The morality of the driver’s act is determined, hereby not by his desires, wishes or his reasons for driving, but by the traffic law that is promulgated by the state and that prohibits careless driving. By the fact that the law is promulgated, agreed upon by all citizens to safeguard life, the law exerts objective extrinsic morality.

Objective extrinsic morality has to do with “human” acts, and as we have seen, it is fundamentally determined by the “nature” of things. Yet, within the sphere of human activity, it is possible to single out some human acts which are indifferent in themselves, but which become invested with a particular moral value because they are object either of a command or a prohibition. Actually, commands or prohibitions seem to increase the degree of the goodness or badness of a human act.

This observation brings us to consider the role “law” plays in determining the morality of some human acts. “Law” is a factor of objective morality, but whereas the “nature of things” is an intrinsic factor of objective morality, “law” is an extrinsic factor.

It is intrinsically good to obey a legitimate authority and it is bad to disobey. But a commanded act besides being what it is becomes an act of obedience or disobedience. Hence, it acquires a new morality, which is evidently extrinsic to its nature. For example, eating meat on Fridays during Lent is indifferent, but when it becomes the object of a Church law, it acquires a new morality (at least for Catholic Christians).

Subjective factors of morality: Conscience

The subjective factors depend upon the subject and they confer upon an action the subjective morality, which can turn out to be profoundly different from objective morality. We define subjective morality as the morality that an action receives from the subject who performs it. These subjective factors can depend on the intellect (that is, the knowledge and awareness the subject has, or does not have, when doing something), or on the will (that is, the freedom and will, involved in performing the action).

The goodness or badness of any action is critically established only when we judge that action in the light of objective principles. This factor of morality focuses our attention on the agent, or subject, of a moral activity. Each one of us is such an agent. By the very fact that we are alive, we are already caught in a web of activities. Through our actions we are making and defining our existence, either as good or bad. At birth we have no moral character to begin with, but we gradually build one for ourselves by the way we live. Our conduct shapes our moral character: the kinds of things we do are either good or bad, and by doing them we ourselves become good or bad.

Our own actions are fundamental in determining the existential quality of our life. But when we are acting, what are the conditions of possibility of those actions? It is possible to act without being aware of what we are doing. These actions, however, are not fully human; they are ‘acts of man.’

Theoretically, it is possible to live without thinking too much of what we are doing, but in this case we should be bold enough to admit that life is not authentic. Life is on the way to authenticity only when we are conscious of what we are doing and why we are doing it. Hence, we act as human beings when we have knowledge of what we are doing. But knowledge alone is not yet sufficient to determine activity. In order to do something I need to will it. Without my will an action cannot represent me either, and thus cannot be fully human. At this point we can say that each one of us is a subject capable of doing many things, but those things are really an individual’s own doing only when there is sufficient knowledge, and sufficient will in performing those actions. We can say that the subjective morality is thus dependent on the intellect of a person and on his or her will.

There is a double aspect of human knowledge: knowledge of something and awareness of something. Knowledge of something constitutes a store of notions that may condition or determine the type of awareness we may have in a particular case. Unless I am aware of what I am doing my action is not fully human; but whether my action is moral or immoral is determined by my knowledge about what is good and what is bad. This knowledge always precedes awareness. Life is not made of generalities but it is a mosaic of small details that very often call for our decisions.

One thing is to know the general principles of morality; another thing is to apply them to the concrete instances of our life. It is part of the dynamism of our intellect not only to perceive the moral principles but also to have the ability of applying them to concrete cases. This ability of our intellect is called “conscience”.

Conscience is our capacity of judging both our actions and the responsibility we have therein. It is our intellect performing the function of judging the moral value, which is the rightness or wrongness of our individual acts. Such a judgment is done according to the set of moral values and principles we hold. Conscience reaches its verdict by means of a deductive process which is analogous to any other logical deductive argument. In actual fact, though, we very rarely spell out the steps for ourselves. Usually we draw the conclusions so quickly that we are not aware that we have been engaging ourselves in a process of deductive reasoning.

Conscience is a subjective factor of morality insofar as it is the supreme and final guide to our actions by commanding or forbidding when the act must either be done or avoided persuading or permitting when there is question of the better or worse course of action without a strict obligation.

Accordingly, the fundamental norm of subjective morality says: “Always act according to the voice of your conscience.” But in case of doubtful conscience one should not act till the matter has been cleared.

Subjective factors of morality: The will

The will is the controlling factor in us. Its function is to issue commands. It can command both bodily acts and mental acts. Therefore, we are held responsible for all that we control by the use of will, both for the acts of the will itself and for the acts of other abilities that the will commands.

Hence, an action from an ethical standpoint fully represents an individual only when it is issued by his or her free will, that is, when it is voluntary. In other words, for an act to become fully human, it is not sufficient that it be guided only by knowledge, but it must also be willed. A voluntary action, as the product of one’s own will, guided by one’s own intellect, is the actual exercise of personal control over one’s conduct. This is responsibility and attributability of the act. The former refers to the agent who is responsible, answerable, and accountable for the act; the latter is proper to the act as it relates to the agent who is chargeable with or gets the credit for the act.

Voluntariness is the measure of the degree of responsibility and attributability. Hence, the subjective morality of an act is modified by the degree the act is voluntary and free. Thus, the following criterion: Whatever strengthens or weakens the will and whatever helps to evaluate the goodness of a physical object, affects one’s voluntariness; whatever hinders a detached deliberation decreases one’s freedom.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Asfaw Semegnish & Kerber Guillermo (eds) (2005): The responsibility to protect, Geneva, WCC Publications.

Benezet Bujo (2001): Foundations of an African Ethic, The crossroad Publishing Company, New York.

Costic, V (ed): AIDS (1987): Meeting the community challenge, Middle green, England, St. Paul publications.

Finnis John (1983): Fundamentals of ethics, Washington D.C, Georgetown University press.

Hoseach Edward G (ed) (1999): Essays on combating corruption in Tanzania, Dar es salaam.

Krasna Beth (ed) (2005): Thinking ethics: How ethical values and standards are changing, Geneva, Profile Books.

Magesa Laurenti (2002): The Moral traditions of Abundant Life, Nairobi, Pauline Publications Africa.

Milton A. Gonsalves (1995): Fagothey’s Right and Reason, Ethics in Theory and Practice, London, Merill Publication Company.

Msafiri Aidan G. (2007): Towards a Credible Environmental Ethics for Africa: A Tanzanian Perspective, Nairobi, CUEA Publications.

Peschke H. Karl (1992): Christian Ethics, Moral Theology in the light of VAT.II, Bangalore, Theological Publications in India.

Rae B. Scott (2009): Moral choices: An Introduction to Ethics, 3rd ed.; Michigan, Zondervan, Grand Rapids.

Sternberg (2004): Business Ethics in Action, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Thiroux Jacques (1995): Ethics; Theory and Practice, New Jersey: Prentice Hall Inc.

Palmer Michael (1994): Moral problems, Cambridge, The Lutterworth press.

Frankena K. William (2005): Ethics, 2nd ed. New Delhi, Prentice-Hall.

Shaw H. William (1999): Social and Personal Ethics, 3rd ed. U.S.A, Wadson Publishing Company.

Bernard Rosen (1993): Ethical theory: Strategies and concepts; Mayfield, California.

Joseph N. (2008): A guide to Ethics, Zapf Chancery, Eldoret (Kenya).

Luciano M. (2000): A guide to Christian ethics and formation in moral maturity, CUEA, Nairobi.

Post a Comment